ALUMNX STORY: Kristie Frederick-Daugherty, 2005 MFA in Writing

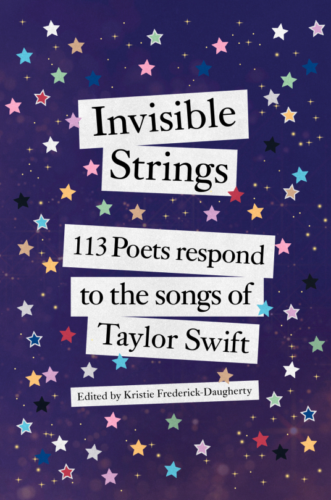

Poet, professor, VCFA MFA in Writing alumnx, and self-described “Swiftie” Kristie Frederick-Daugherty (W ’05) has dedicated her PhD thesis and her new collection, Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift, to the linguistic art of singer-songwriter Taylor Swift.

Poet, professor, VCFA MFA in Writing alumnx, and self-described “Swiftie” Kristie Frederick-Daugherty (W ’05) has dedicated her PhD thesis and her new collection, Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift, to the linguistic art of singer-songwriter Taylor Swift.

Frederick Daugherty has a theory that anyone who loves Taylor Swift would also love contemporary poetry. As a PhD candidate in Literature/Criticism at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania, her dissertation examines how Taylor Swift’s lyrics intersect with contemporary poetry, and how we can use music to drop the veil around poetry and engage more readers. Launching off of her studies is her December 2024 collection with Penguin Random House, Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift. In the collection edited by Frederick Daugherty, 113 poets were given a Taylor Swift song and responded to her lyrics with their own poem. Poets include Naomi Shihab Nye, Maggie Smith, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Kate Baer, amanda lovelace, Tyler Knott Gregson, Jane Hirshfield, Joy Harjo, Mary Jo Bang, Diane Seuss, and more, along with VCFA voices such as MFA in Writing faculty Natasha Sajé and Betsy Sholl and former VCFA faculty member Robin Behn.

In addition to her publications, Frederick Daugherty is set to soon launch The 113 Poets Foundation. Based off of the work started in Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift, the foundation will aim to support working poets with the mission of making poetry more accessible to learners everywhere.

VCFA spoke to Frederick Daugherty about the power of poetry, the power of Taylor Swift, and the power of poetry education. Read the interview below, and learn more about Kristie Frederick-Daugherty’s collection at kristiefrederickdaugherty.com.

The Interview

Q: How did Taylor Swift come into your life?

A: That goes way back to 2009. My daughter Ellie was 11. I’m not a fan of country music, but she was playing something on her CD player, and I heard this voice singing “Teardrops On My Guitar.” I said, “Who is that?” The lyrics were something different, fresh. Swift carried the metaphor throughout the song. And Ellie said, “It’s Taylor Swift.”

In 2009 Taylor brought the first show of her first headlining tour to Evansville, Indiana. She had the very first show right here in Evansville and of course we got tickets. Seeing Taylor in that concert, it was apparent. I thought, “She’s for real.” She can really spin a song. She can write like no other.

Taylor is always different in each album. Taylor’s albums show her ability to just reinvent the self. With every album in some way she deconstructs to construct. Yet all of her discography links, and then reaches hundreds of millions of people. What she’s doing is unprecedented.

Q: You’re currently writing a dissertation about how Taylor Swift’s music intersects with the work of contemporary poets working today, and how we can use this line of thinking to get more readers interested in poetry. Can you talk more about the scholarship you’re engaging in?

A: I read and write contemporary poetry, and as I listened to Taylor Swift, it occurred to me [that poets like] Molly Peacock and Diane Seuss are doing this.

People who listen to Taylor are very trained by Taylor to find allusions and to find symbols. And you know, they might not be calling it an allusion. They’re maybe not calling it a symbol, but that’s what they’re finding, because she has trained them to find connections. Swifties call them “Easter Eggs.” I was interested in that, because generally speaking, people say, “Well, I can’t read poetry. I don’t understand it.” It’s because they’re thinking that poetry is written in some kind of “old” vernacular.

But poetry has its roots in music. I mean, the word “lyric” derives from the word “music,” and that’s where poetry started. And then [poetry] became something considered esoteric in a way, but that’s not what contemporary poets are doing. In short, anybody who loves a Taylor Swift song would love a poem by Diane Seuss or Maggie Smith. That’s kind of where my dissertation comes in. Let’s look at some contemporary poets. Let’s look at some of their poems and see how the moves in Taylor Swift’s lyrics are like the moves in contemporary poetry in order to move poetry back to where it started.

Q: Would you ever want to teach a Taylor Swift poetry class?

A: Oh, absolutely. I’m sure that’s probably going to happen.

I can easily imagine the focus this class would take. For instance, Diane Seuss, she has a poem in her new book of modern poetry called “Ballad,” and it’s so very dramatically similar to “I Can do it With a Broken Heart” [by Taylor Swift]. That’s how I would teach; I would take a poem and then [analyze if] it’s thematically the same, or compare how some of the literary devices are the same as her song. [The song] “Fortnight” is a masterclass in enjambment. It would be interesting to pair that with a poem.

Q: And how did the idea for your new collection, Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift, emerge from your thoughts and study around Taylor’s lyricism?

Q: And how did the idea for your new collection, Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift, emerge from your thoughts and study around Taylor’s lyricism?

A: The catalyst for the book came when she announced [the album] The Tortured Poets Department at the 2024 Grammys.

She said the title The Tortured Poets Department, and I thought, “Wow, how can contemporary poetry enter this conversation?” Because this is a great moment to increase our readership and to also acknowledge Taylor for her writing ability. How can we as poets say, “We validate you and we are not the gatekeepers of what poetry is.”

And the response was amazing. I could not believe it when I started to write to these Pulitzer Prize winners, Pulitzer Prize finalists, US Poet Laureates, [who said] “Yes, yes, yes, I would love to do this.” I didn’t put out a call, I solicited… but because the poetry world is not that big, word got out. I had several poets who wrote and said, “Do you have room?”

We weren’t originally going to have 113 poets—it wasn’t going to be that big. It started with 89 poets, and then when I started getting [more poets] emailing me, I thought, okay, 113, with 13 being Taylor’s number.

Q: Why do you think so many poets jumped at the chance to work on this collection?

A: That’s a really great question, and I talk about that in my intro. I was trying to find the focus of my intro, and I was talking to Diane Seuss, and I said, “Why do you think so many people said yes?” And she said—she’s a friend—she said, “I said yes not just because you asked me to do it.” And she also said, “But you know, you’ve brought us together, and I think this is a way for poets to come together with some joy and celebration.”

So often as poets… poets do a lot of heavy lifting. People turn to poetry in times of grief and in times of love—in times of war. Poets bear witness to these things. So I think this was a chance to have some fun.

I 100% know that so many of [the poets] love Taylor. The majority of them already had a great respect for Taylor and what she’s doing, and that illustrates Taylor’s ability to bring people together through words. Jane Hirshfield is in the book, and Jane told me in an email, she said, “I do not usually say yes. I’m saying yes.” The book actually concludes with Jane’s poem. It’s a knockout.

It was just a lot of magic to it. It’s the Taylor Swift effect. What she can do with words has the ability to bring people together. And it really did. Sir Jonathan Bate, the world’s leading Shakespeare scholar, wrote the foreword. In it, Bate calls Taylor a real poet.

Q: What kind of linguistic power does Taylor Swift have?

A: Take her concerts, for example. People say the concerts are “life-changing.” What is life-changing is singing along with 75,000 people who know all the words. It’s the biggest and most public way that you’ll ever share language. Because language is so often an “alone” event. Everyone might read the same novel, but you read it alone. People read the same poems, but you read them alone. Her words have reached hundreds of millions of people who listened, at one point, alone to Swift’s songs. Then you get in the stadium with 75,000 of them, and you’re all singing together. Not only are you now sharing the words, those words bring back memories. Her eras bring you back to “Oh I was getting married” when “All Too Well” came out or “I was giving birth to my child when “Speak Now” came out.” That’s the magic of her music.

Q: And what kind of reader impact are you hoping for with this book?

A: NetGalley reviews are coming in really strong. Yesterday, someone wrote and said, “I wouldn’t have picked up a book of poetry, but I love [this].” People are reading these poems and these contemporary poets that normally they would think they couldn’t understand. They’re making the connections.

I hope that people love it, and I hope it brings new readers to contemporary poetry.

Q: Out of the collection has emerged The 113 Poets Foundation. While the foundation is still in the beginning stages of its work, can you speak more about the foundation and what its future goals are?

A: I have created the 113 Poets Foundation to continue this mission of making poetry accessible to a larger readership.

I wanted to make sure that the book gave back to the poetry community and to poets. I want to support poets, poetry, and small, independent, not-for-profit presses. That would be my dream, that we can provide funding for the small heartbeat of the poetry world. It is also my dream to be able to provide some sort of support for poets as well, such as travel stipends to get our poets out into universities and high schools.

One concept with this book [and foundation] that I’m working on is uploading a lesson plan for every poem from the book. Ideally, educators could go to the website who, for example, love the poem written by Maggie Smith, click, and there’s a lesson plan that they can use in their classroom. So that’s something I really want to see take off from the foundation—the ability to make it easier for educators to incorporate poetry into their lessons.

Q: What advice would you give to your peers on following their passions?

A: I would say: lead with your heart. And I would quote Taylor, actually: “The worst kind of person is someone who makes someone feel bad, dumb or stupid for being excited about something.” As I started asking poets if they wanted to respond to a Taylor Swift song, I knew many, many poets know the value of Taylor’s words and the complexity of her lyrics, but I of course knew not all of them would. But I led with my heart, and I wasn’t afraid at all to let my enthusiasm and passion show. Just just go with your heart and do what you love and do it in a way that’s true to your own vision. That’s the only way to get people to believe in your words.