ALUMNX STORY: Benjamin Zervigón, 2024 MFA in Music Composition

VCFA MFA in Music Composition alumnx and 2024 Center for Arts + Social Justice Fellow Benjamin Zervigón (MC ‘24) has not only continued the work he started at VCFA, but expanded upon it since graduation.

VCFA MFA in Music Composition alumnx and 2024 Center for Arts + Social Justice Fellow Benjamin Zervigón (MC ‘24) has not only continued the work he started at VCFA, but expanded upon it since graduation.

Zervigón was one of three 2024 VCFA Community Engaged Fellows. Through the Center for Arts + Social Justice Fellowship program, Zervigón received a $5,000 grant to be used in support of work that exists in collaboration with an existing nonprofit organization, agency, or other collective on a project with mutually-beneficial outcomes.

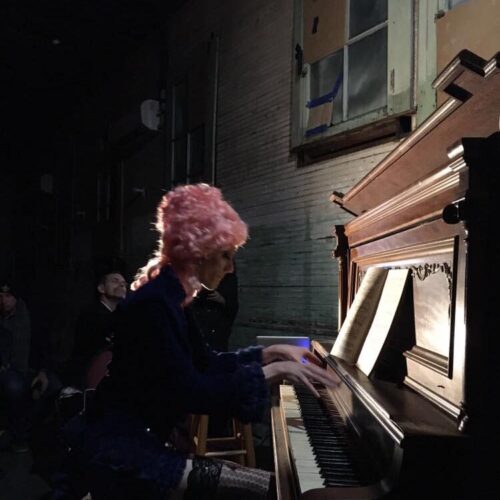

“While in my Community Engaged Fellowship with the Center for Arts + Social Justice, I organized a concert entitled “Lineages,” which was presented last year [in 2024] at the Historic New Orleans Collection (HNOC),” explains Zervigón of his 2024 Center-supported work. “This concert featured music by five generations of New Orleans musicians, including Mahalia Jackson, Roger Dickerson, Moses Hogan, Christopher Trapani, and myself. This concert served as a rallying point for the community to unite around our shared love of New Orleans scholarship. Throughout the process of planning this concert, we created new editions of some endangered scores composed by Mr. Dickerson, as well as archival research at the HNOC to illuminate the connections between each of our practices.”

generations of New Orleans musicians, including Mahalia Jackson, Roger Dickerson, Moses Hogan, Christopher Trapani, and myself. This concert served as a rallying point for the community to unite around our shared love of New Orleans scholarship. Throughout the process of planning this concert, we created new editions of some endangered scores composed by Mr. Dickerson, as well as archival research at the HNOC to illuminate the connections between each of our practices.”

“I am grateful to VCFA for providing us with financial support, encouragement, and professional development opportunities,” continues Zervigón. “Throughout my fellowship, I greatly benefited from presentations organized by Mary-Kim Arnold (W ‘16), Dean of the Faculty & Academic Affairs, on subjects ranging from engaging with archives to refining and defining one’s own personal practice. In addition, I engaged with my fellow fellows, sharing setbacks and milestones with each other as well as providing critique and support for each other.”

This 2024 concert and collaboration codified Zervigón’s professional relationship with Dr. Tara Angelique Melvin. Dr. Melvin and Zervigón both serve as artistic directors of the Alluvium Ensemble in New Orleans. As musicologists, the two have been inspired to continue their work and write about the rich history of New Orleans music.

This 2024 concert and collaboration codified Zervigón’s professional relationship with Dr. Tara Angelique Melvin. Dr. Melvin and Zervigón both serve as artistic directors of the Alluvium Ensemble in New Orleans. As musicologists, the two have been inspired to continue their work and write about the rich history of New Orleans music.

Since his fellowship year and graduating from VCFA in the summer of 2024, Zervigón has been continuing his research into “the establishment and subsequent dissolution of New Orleans’ 19th century musical institutions,” and is working in collaboration with Dr. Melvin to write works that capture a comprehensive history of New Orleans Music—a history that aims to undo the repressive effects of post reconstruction era racism and white supremacist power structures. The pair are currently outlining the start of a textbook.

Now, in 2025, Zervigón and Dr. Melvin are supporting the premiere of Morgiane, a landmark opera written in 1888 by renowned New Orleans composer Edmond Dédé. Interested viewers can see the historic work at Jackson Cathedral in New Orleans on January 23, followed by performances in Washington D.C. on February 3, New York City on February 5, and finally College Park Maryland on February 7.

But why did it take nearly 150 years for this work to see the stage? Zervigón and Dr. Melvin are trying to answer this question, starting with a powerful “written analysis of the Philharmonic Society of New Orleans—a Creole led orchestra of 19th century prominence—as well as the life of Edmond Dédé.”

Engage with and support Zervigón’s important post-VCFA, post-Center work by reading Zervigón and Dr. Melvin’s article “Creole Awakenings” below.

Creole Awakenings

by Benjamin Zervigón and Dr. Tara Angelique Melvin

Creole (adj.): of the place. Native to the region.

2025 will see the premiere of Morgiane, a landmark opera by renowned New Orleans composer Edmond Dédé written in 1888. So why did it take 150 years for this work to see the light of day? To understand Dédé, you need to understand the world he came from.

I. The Creole Romantics

Born only thirty years after the first presentation of opera in North America (1792, Andre Ernest Grétry’s Sylvain in New Orleans) and thirty years before the abolition of slavery, Dédé lived through perhaps the most extreme period of cultural transformation in New Orleans history. The shifting tides of this newly American city, which still maintained a unique sense of cultural autonomy, posed challenges to the long established cultural infrastructure of New Orleans which had raised Dédé.

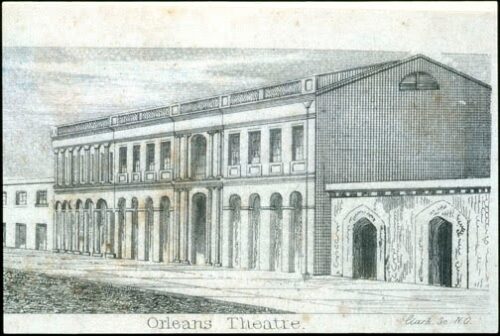

In the earliest days of Dédé’s life (1827-1903), the Théâtre d’Orleans was staging the American premieres of operas such as The Barber of Seville, Le Comte Ory as well as four operas by Rossini. These performances did not happen in a vacuum. They came out of a closely knit musical community which, unique for its time, was created by people of African descent who sought out great performers of every race, creed and sex. This community spirit institutionally manifested in Charles-Richard Lambert founding the Philharmonic Society of New Orleans- the first such society in America not directly attached to an opera company. While the exact founding date is not currently known, the Philharmonic Society became a vital cultural institution throughout the 19th century, performing recitals, concerts, regular rehearsals and even national tours in the summer. Many of the musicians in the society were teachers, composers and conductors themselves. Together they created not just a musical scene, but an enduring institution that supported the artistry of the day- attracting the attention of all New Orleanians as well as global audiences. Maestro Charles-Richard Lambert, a New Yorker settled in New Orleans, became the patriarch of one of the city’s most enduring musical dynasties. His prominent roles as a music educator and conductor codified him as the model of the Creole Romantic Composer and the father of the Creole Romantic movement.

Charles-Richard Lambert, conductor of the Philharmonic Society

Born between the transatlantic slave trade and European classicism, Creole Romanticism encapsulates the culture and varied musical language of the people “of the place.” Often utilizing popular dance forms of the day, such as waltzes, music of this movement can occupy the smallest or largest space and form. From huge orchestral spectacle in the concert hall, to holy music, to intimate dance music in the home or salon, Creole Romantic music is imbued with passion, contemplation and joy. The operas of this period were written on original libretti, portraying locales familiar to the composers and performers such as the markets of Senegal or the streets of New Orleans. Consistent throughout the composers of this movement are fixations on rhythmic variety, thick musical textures and long, virtuosic lines.

Video Description: Tyrone Chambers II and J.T. Hassell Perform Samuel Snaër’s Rappelle Toi live at Holy Name Cathedral

Continuing their fathers legacy, Charles-Lucien and Sidney Lambert dazzled audiences with finely wrought salon music. Meanwhile, as the mid-century approached, Samuel Snäer was regularly staging original masses at St. Mary’s Cathedral as conductor of the Philharmonic Society. The city’s taste for opera had only grown. At the thriving Opera d’Orleans, St. Domingue refugee and founder of Opera d’Orleans, John Davis brought in renowned French conductor Eugene Prevost (a Prix de Rome winner among other accolades). Under Prevost’s baton, the career of Ernest Guiraud was launched- staging his first opera at just fifteen years old. Guiraud eventually left New Orleans to teach at the Paris Conservatoire where his pupils included a young Claude Debussy. Edmond Dédé, son of Philharmonic Society clarinetist and military band leader Basile Fils Dédé, too studied under Prevost, refining his skills as a virtuoso violinist and composer. The cultural relationship between France and New Orleans remained strong even after annexation by the United States. In the 1840s Victor-Eugene McCarty became one of the first Black men to enter the Paris Conservatoire before returning to the U.S. to serve as a leader in Reconstruction. New Orleans continued to produce international level performers long into the 19th century.

St. Mary’s Catholic Church, regular home venue of the New Orleans Philharmonic Society

Théâtre d’Orleans. Photo credit: the Historic New Orleans Collection

This glut of musical riches seemed unstoppable. However, the increasingly regressive conditions imposed upon New Orleans by the United States following the Civil War made it increasingly difficult for Creole musicians to get the respect and recognition they rightfully deserved. Institutions such as the Philharmonic Society had to deal with new segregation laws, splitting their audiences and their musicians. Hence, a precedent of “leave for success” became more and more the norm. In the 1840s Dédé ceased his studies in order to travel to Mexico to earn money in pursuit of his career. War in Mexico forced him back to New Orleans where he worked in a cigar factory- eventually saving up enough money to permanently relocate to Bordeaux, France in 1855. (Bordeaux at the time was quite attractive to people of color seeking greater opportunity in no small part due to the presence of community leader Louise Chancy, the daughter in law of Toussaint Louverture.) By the time of the implementation of Jim-Crow segregation in the United States, the popular national narrative of music history within the States had essentially erased this vital canon of composers’ legacy.

Video Description: Edmond Dédé’s Rêverie Champêtre

Composer, conductor, violinist Edmond Dédé

II. Continuing the legacy in the 21st Century

“This [Creole Romantic] music is important to share with the world because it shows us that we are more similar than we are different.” -Givonna Joseph

While the history outlined in the first half of this article may feel distant to most readers, here in New Orleans the legacy of the Creole Romantics is felt deeply by local musicians. The reach of composers like the Lamberts and Dédé is an inescapable facet of our pedagogical history. From icons of the 20th century like Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, his composition studio-mate Camille “the Louisiana Lady” Nickerson and big band innovator Dave Bartholomew, to contemporary masters like Roger Dickerson and Ellis Marsalis Jr. the memory of these great composers has been carefully stewarded by a mighty handful of musicians. Perhaps the most significant keeper of this cultural memory is mezzo-soprano, music historian and founder of Opera Créole, Givonna Joseph.

B.K.Zervigón and Dr. Tara Angelique Melvin sat down with Ms. Joseph at her home in the Garden District to discuss Opera Créole’s staging of Dédé’s Morgiane as well as the endless work of revealing the 19th century New Orleans Canon to a broader public.

Ms. Joseph first identified her calling of Creole musicology while she was an undergraduate voice student at Loyola University in New Orleans. Upon hearing the music of the Creole Romantics for the first time in a studio class, she was shocked that she had never heard this repertoire before. She was hooked on the music and determined to aid in its dissemination.

“I was always told growing up, ‘You’re weird. Black girls don’t sing opera.’ So at the time, I said ‘Okay- I’ll be weird then.’ but once I started finding out about all these great [black] singers and composers from the 19th century and in some cases even earlier, I realized what I’d always felt. This is who I am. This is in my bones.” -Givonna Joseph

Beginning her search in Tulane University’s Armitage Archive as well as the Historic New Orleans Collection, Ms. Joseph quickly began collecting scores, collaborating with other historians and nursing ideas of future productions. Being Creole herself, formalizing her knowledge of this hidden Canon taught Ms. Joseph about herself.

“It was as if it was genetically programmed into me. These pieces just started coming to me. Each time they present themselves, it is for a specific purpose.” -Givonna Joseph

It was in her capacity as education director for the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra that Ms. Joseph began work staging pieces of the 19th century Creole Romantic Canon.

“I started looking for other recordings to hear these works. I saw Dédé being performed in Colorado. Colorado? Why aren’t we presenting this here [in New Orleans]? We have to play this music here.” -Givonna Joseph

Ms. Joseph was able to execute a small number of programming and educational events with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra. However, it quickly became evident that the reactionary, segregationist roots of our now withered 20th Century Cultural Institutions prevented her from meeting her goals of regular presentations. It was then that she realized she must double-down and follow the model of her ancestors. When existing Cultural Institutions are exclusionary, it is incumbent on each of us to create new institutions. Just as Charles-Richard Lambert endeavored to create a safe, creative space for the musicians of New Orleans with the Philharmonic Society, Givonna Joseph has done the same with her Opera Créole. One step at a time, Ms. Joseph is determined to create the infrastructure this music desperately needs.

Over the course of its fourteen years, Opera Créole has been rapidly growing and fastidiously collecting scores by Creole Romantic Composers as well as composers with tight aesthetic and social kinship to the Creole Romantics such as Joseph “Chevalier de Saint-Georges” Bologne and William Grant Still. Throughout any given season, Opera Créole regularly presents evenings of intimate song, performing both as Opera Créole’s Mainstage and as guest artists at significant cultural events such as Jazz Fest and the Whitney Plantation Gala. In addition to song nights, Opera Créole has also partially staged productions of Tremonisha by William Grant Still, an original opera entitled The Lions of Reconstruction as well as La Flamenca by Lucien Lambert. While primarily based in New Orleans, these concerts occur in New Orleans and beyond.

Video Description: Opera Créole’s 2017 production of Lucien Lambert’s 1903 opera La Flamenca

With as much musical archeology as this repertoire requires, the work of scholarship is often half the battle for Opera Créole.

“We work to prepare editions. Many of the scores we work from are in very poor condition. Our mezzo-soprano, Valencia Pleasant, has spent a great deal of time creating these new editions for current and future use.” -Givonna Joseph

This year, Ms. Joseph has embarked on the company’s biggest adventure yet: the staging of Edmond Dédé’s Grand Opera, Morgiane.

“Morgiane tells the story we need to hear. It’s a story of resistance and love. A young woman is forced to marry the Sultan- the Sultan has no idea she’s his daughter! She refuses. She stands on her own two feet and says no. And what happens in the end? She succeeds and everyone has a party. That’s the New Orleans spirit even in a work this old.” -Givonna Joseph

To achieve this massive feat, Ms. Joseph has teamed up with another New Orleans native, one who has built a career for himself abroad, Patrick Quigley of Washington D.C.’s Opera Lafayette. Together, they have been sifting through Dédé’s multi-hundred page hand-written manuscript, creating a new type set edition. By applying the principles of opera staging associated with new production, the team hopes to breathe life into this neglected work. It’s already beginning to attract international attention.

“Opera Bordeaux reached out to us recently about the manuscript. *laughs*” -Givonna Joseph

Bordeaux, of course, was the home of Dédé at the time he composed Morgiane. In Dédé’s mature years, he gained quite the reputation and influence in France as a composer and conductor of multiple prestigious orchestras. So why has it taken this opera so long to see the light of day?

“Well, it’s like my daughter Aria says, ‘Hello! Racism! Duh!’” – Givonna Joseph

While racism is undoubtedly responsible for the neglect and erasure of the Creole Romantic Canon, it is important to note that there was indeed a production of Morgiane scheduled within Dédé’s lifetime. Musicians of this era worked hard and succeeded in presenting milestone achievements in the repertoire. The story of why Morgiane’s premiere was canceled is one that may feel painfully familiar to many New Orleanians.

Morgiane had originally been set to premiere in New Orleans in the late 19th century. Dédé was excited to finally see his largest work be born in the city that birthed him. In order to aid in the rehearsal process and see his opera come to fruition, Dédé boarded the passenger freighter known as the Marseille. Dédé was so successful in France that he was able to afford a luxurious first class suite. He was the only passenger in first class on this particular voyage, a rarity for this passenger freighter known for its opulent clientele. In a cruel twist of fate, the ship was critically damaged by a hurricane just as it entered Dédé’s warm home-waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Stranded at sea for days, another passing vessel was eventually able to rescue the marooned passengers, though some 20 people likely died in the process and subsequent quarantine period. The ship then docked at Galveston, Texas- stranding Dédé and forcing him to take a long journey back to New Orleans and subsequently Bordeaux. Due to Dédé’s absence during the rehearsal period, Morgiane’s production was canceled. It is often posited in the oral history that this was the same journey that caused Dédé to lose his cherished Cremona violin. A cruel homecoming indeed.

Now, some 150 years later, Dédé has another shot at a homecoming. On January 23, 2025 in New Orleans, Louisiana, Opera Créole will present Morgiane to the audience he had always hoped to reach. This will be followed by an East Coast tour to Washington D.C., Maryland, and New York City from February 3-7. For more information on Morgiane as well as other future productions, please visit www.operacreole.org.

III. Call to Action

Ms. Joseph’s organization has taken significant strides over the last decade to bring many previously unknown operas to life on stages all around the world. Over the past decade the organization has produced operas like Lucien Fils Lambert’s La Flamenca and La Spahi. Morgiane is the company’s latest and by far grandest production to date and through their work they have partnered with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra, Opera Lafayette, Cincinnati Opera and the Historic New Orleans Collection to ensure this work gets the honor it deserves.

No one takes this work lightly, least of all Givonna Joseph of Opera Crèole. She asserts that her goal and dream is that others take up the mantle to help uncover this hidden history of the thriving classical music scene in the United States. She’s not the only one. Organizations like Black Administrators of Opera, Darryl Taylor’s African American Art Song Alliance and the Black Opera Research Network take the erasure of Black composers seriously. They tirelessly work to identify and uncover composers whose works have largely gone unseen while simultaneously studying and amplifying what they find. This should not be the work of a small group of people. This history is as much the history of classical music as Hector Berlioz’s work and deserves the same attention and rigorous study. That won’t happen without curiosity and time. We all have the power to change the narrative about what classical music is and who belongs in the Pantheon of artists worthy of study. If these composers have taught us nothing, it is that art is a communal activity and we need everyone to ensure that classical music remains alive and relevant.

How?

Scholars, use the aforementioned curiosity. What is the history of your region or your favorite region? Are there gaps in scholarship? Is the history complete? Who was your favorite composer’s favorite composer? What was a popular musical or dance genre during your favorite time period?

Musicians, Theorists and Composers, who are your favorite musicians’ favorite musicians, living or dead? Who influenced whom? Who were the contemporaries of those musicians? Were there any other musical movements going on? Never assume because you have not heard of someone that the music is bad or isn’t worth studying and understanding. If you have the ability, knowledge and resources, go deeper. Pick a handwritten piece of music from IMSLP or a private collection such as the Historic New Orleans Collection, ask for permission if you need to, and make a transcription. Most of what separates this work from the public is the fact that it cannot be read and isn’t played. Organizations like the Historic New Orleans Collection have research grants that often pay thousands of dollars to encourage people to study their collection. Professors often receive discretionary funds as well. If you’re a professor, lighten your burden and make it a class project.

Performers, be curious. Explore the musical world more broadly. Are there regional composers you may not have heard of? Dig a little and get out of your comfort zone. Is there a piece of music you really love? What do you love about it? Where did that piece come from? Who are the contemporaries of the composer or the artists it was composed for? Commit to learning a piece that is totally new to you or others. If you are in school, commit to learning a new piece every semester, trimester or whenever new music is assigned. Present those pieces when possible.

Teachers and advocates, do not assign the same songs from the same composers. Assign little performed songs from the composers you know or songs that are new to you. Commit to assigning each student a new composer. If you teach operatic, orchestral, or song history or literature classes, add a new composer to the class. If you have a seminar class, introduce new composers as part of the seminar.

Academics of all disciplines, research and write on topics that interest you. Question the musical world around you and why the Classical Canon is the Canon. Write about it. Write about composers you’ve discovered. Write textbooks, chapters, articles and blog posts. Writing creates interest and even descent is a good thing. It breeds discussion about where classical music is going and who is part of history.

Lecturers and speakers, have conversations. Schedule discussions about a subject, composer or historical context you may be interested in. Invite questions. Invite discourse. If you have a podcast or social media channel, use it to talk about a topic that interests you or information you think is cool.

Audience members and donors, engage your curiosity. Question why a new-to-you composer is not being presented alongside composers of the Canon. Oftentimes, companies believe there is no interest in presenting works that are not “tried and true.” The automatic assumption is that no one will support a piece of music they do not already know by heart.

Producers, if you have the capacity, interest and passion to produce an opera, please know that you do not need to be the Metropolitan Opera or La Scala to produce a show. In fact, it does not need to be a grand undertaking. Opera is relatively easy to put on if you have the formula. You can start with open rehearsals, concert performances and workshops. Sets and costumes are not as important as simply getting the music heard and into the public sphere.

Now is the time to act and lead.