Barbara Yontz, 2004 MFA in Visual Art

“One reason we have done the exhibitions, and I do personal work around these issues, is to humanize people who are incarcerated to those on the outside.”

– Barbara Yontz

Visual Art (’04) alumnx Barbara Yontz has spent years as a conceptual artist making sculpture with natural materials. Most recently, however, her work has been centered around process, intention, and collaboration—with one of her most unique collaborations to date being with the men of Unit 2.

Visual Art (’04) alumnx Barbara Yontz has spent years as a conceptual artist making sculpture with natural materials. Most recently, however, her work has been centered around process, intention, and collaboration—with one of her most unique collaborations to date being with the men of Unit 2.

Since 2013, Yontz has been teaching and working with the men living on Death Row at Riverbend Maximum Security Prison in Nashville, TN. Together, they create collaborative art pieces where each artist contributes a small part of a larger, community work. Their art has resulted in exhibitions such as Unit 2 Voices: Artwork from Death Row (hosted at St. Thomas Aquinas College in September 2015) and projects like The Love Letter Series (a group of drawings conceived as individual letters to each of the 11 men of Unit 2).

We recently spoke to Yontz about her work with Unit 2, working with incarcerated artists, and the path to art and social justice.

ON FINDING THE PATH TO ART AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

My interest in social justice was always part of my journey. When I started college in the 1970s, it was not a part of the discussion in art, at least not where I studied. This created a lot of conflict for me, which is why I think I moved into the personal/psychological/historic realm of exploration. I was working with several issues that came to be defined as “feminist” even though few were talking about it at the University of South Florida at that time. After the BA in Art, I pursued a Master’s in Art Education because it was in that program where there seemed to be more concern for integrating art in the community.

The actual “social justice” practice evolved, like most everything else in my life. I’ve always done volunteer work and used art to engage others, but my personal practice and what I called volunteer work were separate. Over the years of making, teaching, researching, and learning, I realized I could merge the two. Vermont College [of Fine Arts] was an important experience in this regard.

ON WORKING WITH UNIT 2 & INCARCERATED POPULATIONS

Over the years from 2006 to now, my interest in incarceration in America, the Prison Industrial Complex, and the realities of the lives of real people who are incarcerated grew.

In the summer of 2013, two of my former colleagues from Watkins College of Art (where I taught prior to moving to NY) had been asked to take a class at Riverbend Maximum Security Prison for the summer. We were all artists, so it was an art class. This is how our first class began. It was only supposed to last one summer, but the men liked it so much they asked for it to continue. We went inside every week, and the class continued until March 2020 when we were shut down for COVID.

That first summer at Riverbend we included a group of students from Watkins College of Art. We began that first summer working on two different types of projects with the men on the inside and students and artists outside:

That first summer at Riverbend we included a group of students from Watkins College of Art. We began that first summer working on two different types of projects with the men on the inside and students and artists outside:

- Collaborative works: In these, one artist on either the inside or outside would begin a drawing, collage, or photograph, then another would take the piece and add something. It would then be returned to the original artist. This process continued until the piece was deemed “finished” by both parties.

- Surrogate projects: In this project, the men on the inside made a list of things they wanted to do but were unable to because of their incarceration. Those of us on the outside chose an event and completed it. Sometimes the things allowed us to do them in community, such as visiting a particular sculpture in a local sculpture park, or another where we made a huge breakfast to the specifications of one of the men, which we then ate. All surrogate projects were documented with photographs that were then brought back inside.

These two projects formed the basis of several subsequent exhibitions. The collaborative project continued even up to 2020.

ON THE IMPACT OF THE EXHIBITIONS AND THE IMPORTANCE THIS WORK

ON THE IMPACT OF THE EXHIBITIONS AND THE IMPORTANCE THIS WORK

There have been a number of exhibitions in different contexts, and the reactions have been different. For the most part, the exhibitions provide an opportunity to talk about incarceration and the death penalty, and to personalize the men.

There are many reasons for doing this as artists and individuals, as well as for all of us socially. Many of these men have been incarcerated for a very long time, most since they were quite young. They really didn’t have much of a life prior to prison. Once inside, the system does most everything possible to keep them invisible—out of sight of the general population.

These classes provide a sense of community, a place where it’s safe to talk openly, a place to share and laugh.

ON HOW TO BETTER SUPPORT INCARCERATED POPULATIONS

All the men in our group would, and do, discuss the importance of a solid and fair education for young people to help deter the possibilities in the first place. Then, the judicial system is constructed so that wealthy people, or those with money and privilege, are able to defend themselves while those who are poor or in minority positions are not. The system does not favor the people who really need it the most.

As far as prisons are concerned, they need rehabilitative and educational programs. One example of this is that Lipscomb University in Nashville has a Conflict Resolution Management Program. They brought someone into Unit 2 to teach the Mediation class. After the class, the men established their own mediation program for inmates and/or CO’s and inmates who had conflict with each other. The program is so successful, it has been expanded to other units and the men are resolving their own conflicts without any administrative influence.

HER ADVICE FOR HER PEERS LOOKING TO ENGAGE IN ARTS AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

Just start with something. It should be something you care about. Do something small and see where it goes. Don’t have any expectations. Don’t think of it as important to your career. Do something you care about, and do something you think will make a difference to someone.

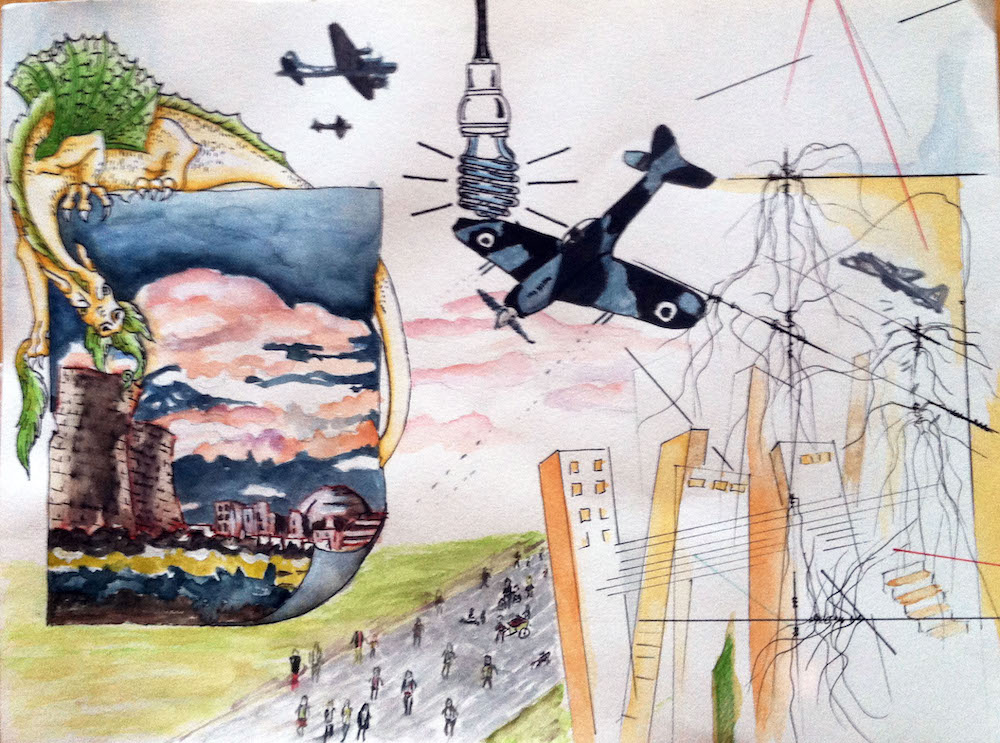

All images courtesy of Barbara Yontz. Her captions for the three illustrations, from top to bottom:

- “This is a collaboration I did with one of the men in Unit 2. He started the project with the light bulb and then we went back and forth about 6 times to get to this end. In each case, we never talked about the project. Each of us responded to what we got.”

- “This is a photo taken by one of my former students at St. Thomas Aquinas College. She was in a graduate program at Arizona State and did an internship in Ghana. She sent photos of her experience at a former slave trading castle. Tyrone (one of our incarcerated artists) added this flower. They did several of these.”

- “This is a large piece—30 x 40—that we did inside the prison with all the men in our group and our three main instructors: Robin Paris, Tom Williams, and me. We worked around a table for about 2 months over the summer.”